Why do Brits Hate the Stock Market?

Lack of familiarity, fear of losing money, and a love of property hold the UK back

I spent half my twenties living in the US, and one thing that struck me was the difference in investing attitudes among my peers. University graduates living in New York and London with high cost of living and high house prices. Yet while my New York peers were content to “max out their 401K” and comfortable and well-versed in investing in the stock market, my London peers were squirrelling away their savings in a low deposit account with the goal of buying an average flat in an average part of London.

Clearly this wasn’t a like-for-like sample, but I’m also far from the first person to notice a difference. Fast forward 15 years, and the UK government was tentatively muttering about reviving an equity investment culture among the public via a sale of its shares in NatWest, the bank nationalised in 2008 in which the government still owns 30%. That seemed to me at best embarrassing, at worst a path to concentrating personal investments in a company that’s generated a measly ROE over the last decade. Thankfully, the new government has put a halt to this sale, but interest in stimulating equity investment among the UK public remains.

As I’ve written before, this is no bad goal. The UK equity market lacks a domestic investor base, either from UK institutions or UK individuals, and there is a reasonable case that this has had a negative impact on UK companies, harming liquidity and limiting their ability to raise capital. On the institutional side, this has been partly attributed to regulatory and accounting changes (I would also add it’s just that ALL investing got more global and the relative importance of the UK economy to the world declined). But on the retail side there’s no obvious single regulatory or tax catalyst.

In fact, investing in stocks and shares is and has been a pretty good deal for UK taxpayers. Since 1987 they have benefitted from a tax-sheltered account for investments, first in the form of Personal Equity Plans, and since 1999, in the form of Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs). ISAs are well known and simple to understand. You put in post-tax money up to an allowed amount each year (currently £20,000) and pay zero tax on subsequent gains or dividends. Do that for twenty years and it’s a lot of tax you don’t pay.

If ISAs weren’t sufficient there have been further allowances available for dividends and capital gains in taxable accounts. The rules are constantly tinkered with – and are much less generous today – but in short, both dividends and capital gains have historically been subject to lower effective tax rates than income.

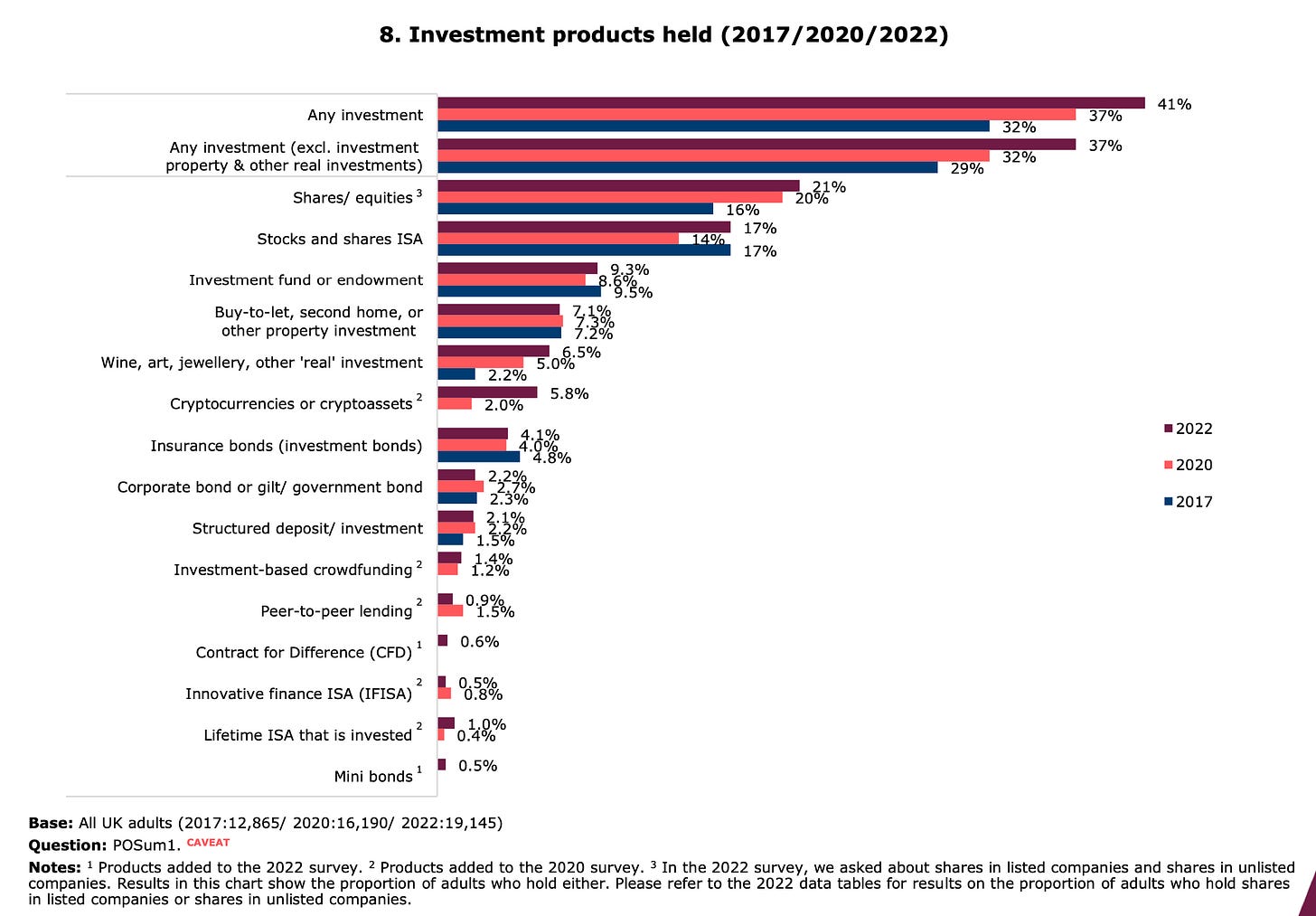

What’s quite surprising then is how few Brits take advantage of this tax wrapper. In its 2022 Financial Lives Survey, the FCA found that 17% of UK adults held a stocks and shares ISA, with 21% holding individual shares directly. Separate analysis by AJ Bell using HMRC data found that 40% of the UK adult population held some form of ISA, but the majority of subscriptions were to cash accounts (59% for men and 74% for women).

With this background, there are a few things to unwrap. First, is it really such a small share of the population investing in the stock market? Second, if we accept it is low, what are the reasons for it? Third, does it matter?

What share of Brits invest in the stock market?

The first question isn’t so easy, as a closer look at the FCA chart shows. It’s not a great survey question. It mixes asset type (e.g. equities, bonds, property) with investment vehicle (e.g. ISAs, investment funds). Everyone who invests in a stocks & shares ISA will invest in either stocks or funds through it. Funds and endowments will be invested in individual stocks and bonds.

We also don’t know how many people own more than one of these categories, so we can’t accurately say what share of the UK population invests in stocks. The best we can do is take the largest of the numbers, 21% of adults that invest in stocks, as a minimum estimate. As a maximum I’d add the share invested in funds to give 21% to 30% as a plausible range.

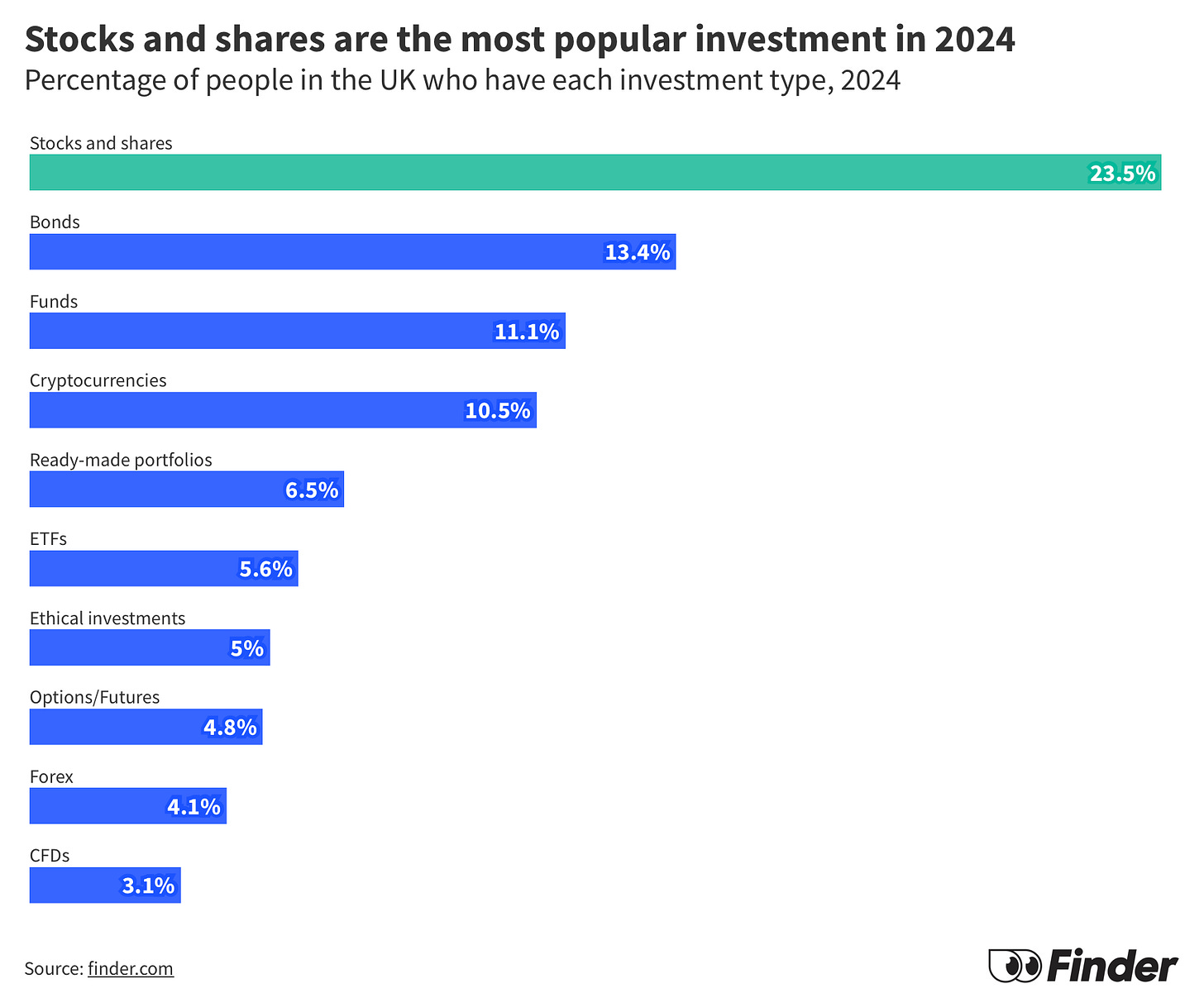

This survey by Finder.com has the same problem, mixing asset type with investment vehicle. Using the same approach as with the FCA data though gives a comparable minimum of 24% investing in stocks, potentially up to c.50% if you assume all funds, ETFs and ready-made portfolios are invested in equities, and no one holds both. That seems very implausible, so I’d stick with 20-30% of UK adults owning stocks and shares as a ballpark estimate (if someone knows more accurate figures, please let me know).

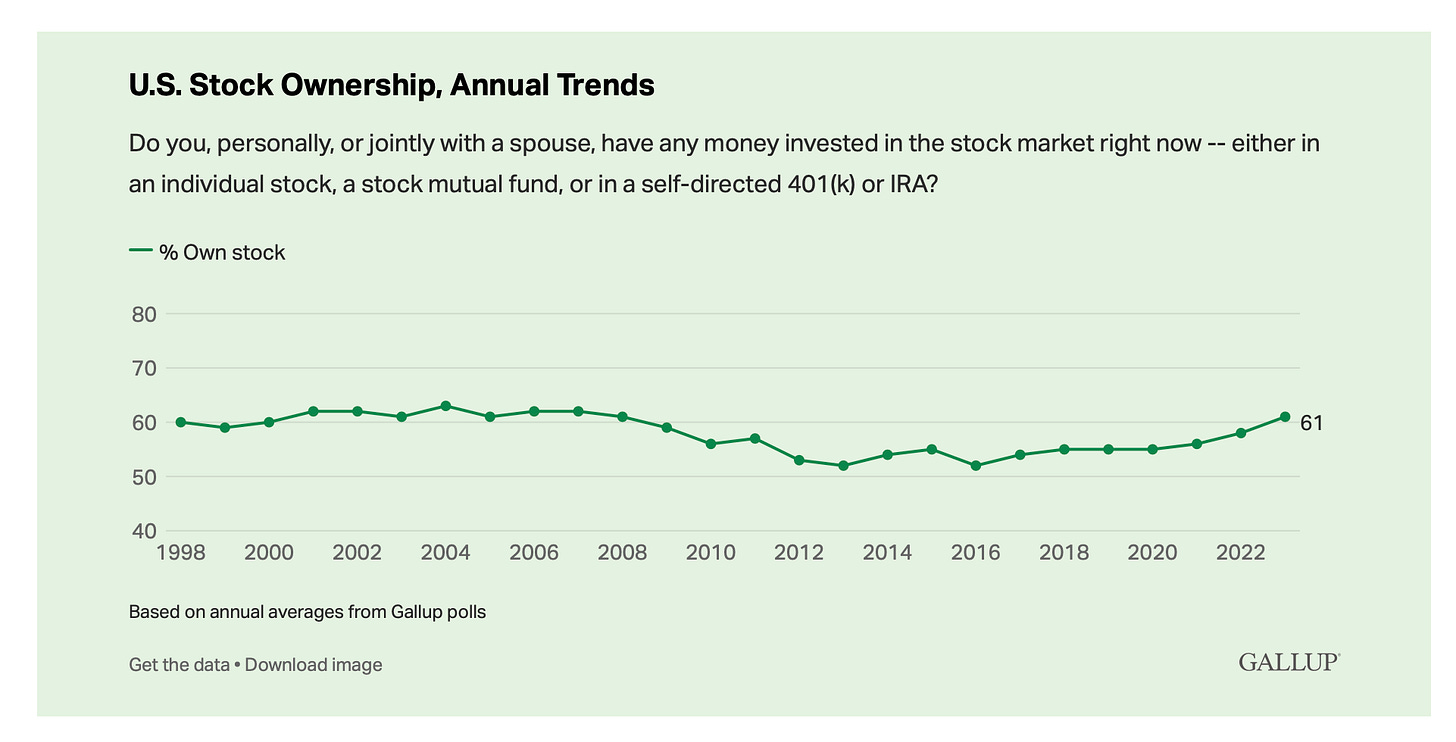

A better question would be to take the approach by Gallup in the US, which asks: “Do you, personally, or jointly with a spouse, have any money invested in the stock market right now – either in an individual stock, a stock mutual fund, or in a self-directed 401(k) or IRA?” Just substitute self-directed 401(k) for self-directed SIPP/workplace pension in the UK. This is a more expansive question than that of the FCA – including as it does retirement assets – which is one reason why the US level of 61% of adults owning stocks is so much higher.

But I don’t think survey design is the only reason for why the US number is roughly double the UK. Self-directed retirement plans (SIPPs) in the UK are much less prevalent than the US 401K, with just under 1 million people having one in 2016, per the ONS. Adding these in doesn’t move the needle much.

Why do so few Brits invest in stocks and shares?

From what I’ve experienced – and you can explore further in this Reddit forum – investing in stocks and shares is much less common in the UK than in the US, and I think that’s due to a number of reasons[1].

For a start, culture looms large. In the UK it is common for people to compare investing in the stock market to “gambling”, with its implicit threat of losing everything you put in. It’s something I certainly heard growing up. But gambling (and it should be noted that the British really like gambling in other areas…) is very different to investing. Gambling has negative expected value – the odds are always tilted towards the house. Investing in stocks, by contrast, should have positive expected value. Holding a diversified portfolio of shares mean owning a share in actual companies that generate profit and grow over time. It is hard to think of a scenario in which the value of all companies goes to zero. If it does, it’s nuclear Armageddon and we have bigger worries.

Closely tied to culture is fear and education. Fear, because people hate losing money and are scared by the prospect of it – and investing after all is about taking some risk. Fear is universal, but education and familiarity with how markets work help overcome it. Still, it takes time and experience, and that’s where culture and history hold us back. A lot of people won’t know anyone who invests in stocks and shares, and if they do, it’s money, and Brits generally hate to talk about that.

I also think the UK investment industry has been woeful in access, innovation and marketing. I’ve written previously about the needless complexity of investing, although that’s a global truth. What I’ve found personally is that investing from in the UK is just more of a pain than from in the US. Opening an account seemed more complicated, sorting out tax was a nightmare, commissions and fees seemed very high, competition for my business seemed low. Where is the e-trade baby in the UK? Where is a compelling ad to open an investment account?

There is also the elephant in the room of UK housing. Only 11% of Brits own an investment fund but 7% own a buy-to-let property. Property is familiar, and at least in London and the South East, has delivered solid returns, particularly if you borrow most of the initial cost. While people in the UK rarely, if ever, discuss stocks, there’s always someone who knows someone who bought a buy-to-let thirty years ago, or amassed a property portfolio for their pension pot. The tax rules are less generous now, and the tailwind of falling interest rates for house prices behind us, but the legacy of property as a go-to investment remains.

Even for those not amassing a property portfolio, the cost of UK housing still influences investment allocation. Those saving for a deposit against a backdrop of tepid income growth and rising house prices don’t want to risk any fall in capital; while the older generation who have housing equity and savings to spare are recycling this into their offspring’s property purchases via the Bank of Mum and Dad, now worth an estimated £9 billion a year. That’s £9 billion that could be invested in companies instead.

Is this changing?

What’s interesting is that this may be starting to change.

For a start, the UK retirement system is seeing a large shift away from defined benefit (DB) plans, in which individuals have no say over asset allocation, towards defined contribution (DC) plans, in which individuals tend to bear greater responsibility for their savings. According to McKinsey, DC membership in the UK has increased from about 1 million people in 2012 to more than 26 million today. Most of this growth has come from people being automatically enrolled in workplace DC pensions that use default asset allocations. However, over time you could see self-directed investing begin to grow as individuals pay closer attention to what is held in their pension pots.

At the same time, a new wave of fintech companies are improving access to investing, either by cross-selling share trading from banking and currency apps (e.g. Revolut) or providing zero commission trading plus an easy customer interface (e.g. Trading 212). Established low-cost fund providers like Vanguard are also gaining ground rapidly (it’s worth noting that Vanguard’s direct to consumer platform only opened in the UK in 2017).

Some of this is beginning to show up in the data. In its 2022 survey, the FCA found a “notable increase in the proportion of younger adults holding investment products”, including a 6% rise in those holding stocks and shares ISAs.

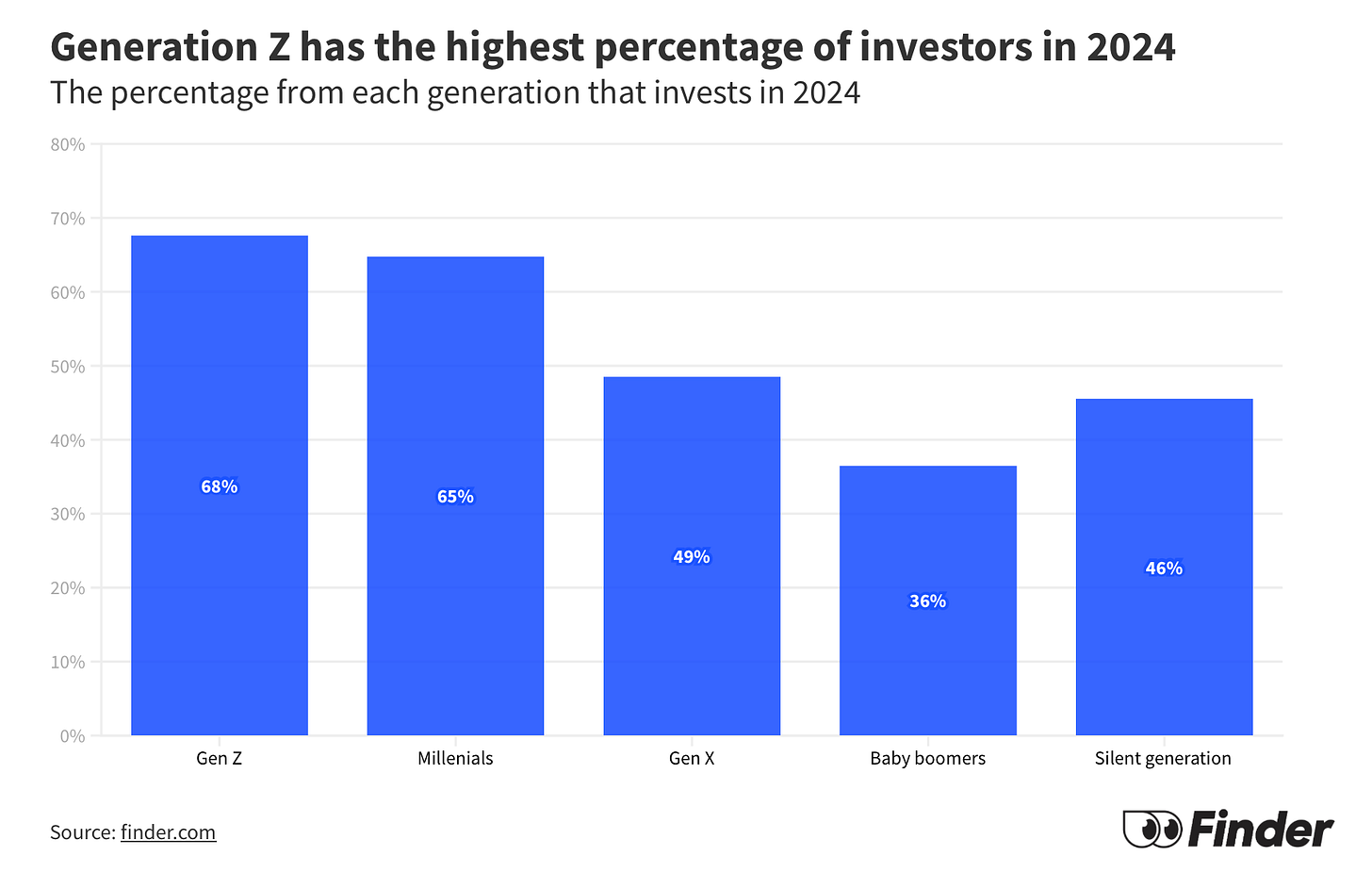

Finder.com found something similar with its later survey, in which Gen Z had the highest percentage of investors in 2024, far outstripping baby boomers. Perhaps Gen Z are the ones to finally throw in the towel on buying a house, and they’re tech-savvy enough to access the new investing apps and buy part of a share of Apple or Nvidia. That, and buying crypto.

Does it matter for the UK?

From a broader economic and social perspective, investing serves two main purposes. It can increase individual wealth, and it can increase the flow of capital to businesses, enabling growth and investment. From a UK growth perspective, we’re most interested in capital to UK businesses. At present though, any additional flows into stocks and shares from UK individuals are not obviously flowing to UK companies.

The recent revival in UK equities has been driven almost entirely by inflows from institutional investors, according to Goldman Sachs. “Retail investors are still not buying: the best that can be said is that the pace of selling has receded,” its analysts argued in a recent note.

Although UK households have maintained high savings ratios, they have put this into cash or fixed-rate bonds given elevated interest rates and are only likely to rotate back into equities once they start to fall, it added.

Of those that are buying stocks, my guess is that much is going into US stocks given brand familiarity, recent performance and access (on many newer platforms, US stocks are just as accessible as UK ones and more promoted). But I don’t think this is a bad thing - it’s building experience, an investment culture and a more risk-taking attitude. This could ultimately lead to more interest in UK domestic companies, and more entrepreneurialism across the UK as a whole.

So, to round this all up there’s some big and complex reasons that hold back stock investing in the UK, but there’s also some tentative signs that these are beginning to shift across generations. That doesn’t mean I’m expecting mass retail flows into UK equities in the next few years; but looking out over 20 years there’s potential for change.

[1] One explanation I deliberately haven’t included is lack of income, which is not because I don’t recognise it’s the primary constraint for many people, but because the comparison I want to make here is the difference in attitudes among those who do have income to save.

It’s a good point. Would be interesting to look into the data on saving rates etc. I’m in the midst of moving house so it will have to wait a few days but I’ll follow up when I get some time. Thanks for the comment!

Could it also be that UK citizens earn less cash after tax, and therefore have less to invest? Meanwhile US citizens save more, and therefore invest more (to pay for medical bills etc)?