The Slow Death (and Potential Revival) of the UK Stock Market

And how a flurry of reforms could revive it

There has been much handwringing over the state of UK equity markets in recent years. Headlines are generally triggered by the failure of London to attract an IPO – the recent poster child for this being Arm (Nasdaq), where the handwringing was further accentuated by the UK government greenlighting the acquisition by Softbank in 2016, which took the UK’s main semiconductor success story off the London market and set in motion the events leading to the company’s Nasdaq IPO.

Alas, 2016 was a different time, in which the UK government was merrily agnostic about who owned what. Fast forward eight years, throw in a pandemic and rising alarm over Chinese domination of supply chains, and you have a far more nationalist approach to the health of the nation’s stock market. Add in long held concerns over the ability of the UK to scale up innovative businesses - combined with lots of time, energy and taxpayer funds going into supporting the growth of smaller UK firms and a UK venture capital ecosystem - and it’s little surprise that reviving London’s stock market is getting more and more policy attention.

The surprise is perhaps that it’s taken so long for the links between private and public funding to get acknowledged by policymakers. There are however now a whole host of reforms in the works, which can only be good news as a means of increasing capital available to UK firms, increasing the investment opportunities for UK individuals, and (perhaps) breaking the nation’s obsession with property as a means of creating wealth.

Is the UK stock market really dying?

Performance and valuations

It’s easy to get caught up in IPO-driven doom-laden headlines, but there’s a genuine question of whether the state of the UK stock market is really that bad.

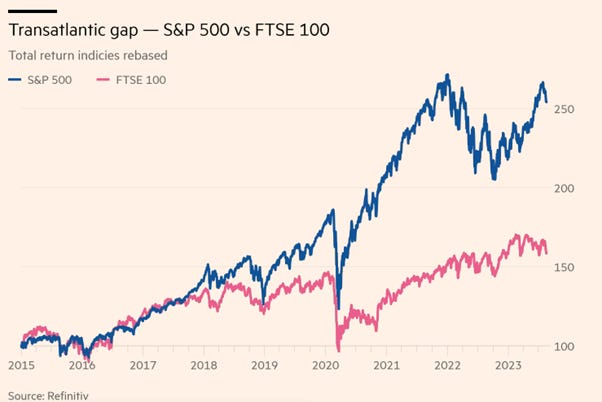

Yes, performance looks dire.

And yes, valuations look cheap.

But a lot of this is simply the US being exceptionally good rather than the UK being exceptionally bad.

And if you adjust for the sectoral composition of the UK market, skewed as it is towards sectors that typically command lower valuations, like oil and gas (BP, Shell), mining (Rio Tinto, Glencore), financials (HSBC), booze (Diageo) and cigarettes (British American Tobacco), the argument that any given company will get a higher valuation in the US looks weaker. Simply put, the FTSE 100 is cheap because it’s full of a lot of companies in cheap sectors (this deserves a more detailed discussion but that’s for another day).

Market size

It’s not just performance and valuation though, the shrinking number of publicly listed firms is also raising concerns. Although the chart below misses seven years of UK data for reasons unknown (there are other sources that show a downward trend during this period, but this was the one accessible and free, and hey, I write this for free…), we can still see a decline from before the financial crisis to today. This has been most acute at the smaller end of the market - the market cap of UK small and midcap companies fell by 40% between 2018 and 2023.

Relative to the size of the economy, UK stock market capitalisation has been on a downward trend since the late 1990s, but the disparity with the US only really starts emerging post 2012. Since that time the UK market has shrunk by roughly a third, relative to UK GDP.

As France shows, which like much of continental Europe has historically had smaller capital markets and more bank-led funding, different countries have different approaches to raising capital for domestic firms. The issue with the UK is less about its absolute levels and more about how the relative importance of the stock market has declined, and whether this is best serving UK plc and the wider economy today.

Liquidity

Where there does appear to be a problem – albeit a less headline worthy one – is in the liquidity of the UK market, tied as it is to the absence of a steady domestic investor base. Using the same source (again, this misses some years but supports a trend that’s cited by many other commentators) we see that the total value of domestic shares traded on UK markets has collapsed from 129% of GDP in 2010 to 25% of GDP in 2022. Liquidity in the US has declined too, but to nowhere near the same extent as in the UK. And in France, well who knows.

Investor base

The falling volume of shares traded has been most acute among small and midcap names, which are traditionally more domestically focused, and which fly under the radar of international investors. Such international investors have come to dominate UK stock market ownership, accounting for 57.7% of quoted shares in 2022. This rise in overseas ownership is the flipside of a collapse in UK institutional ownership, with UK pension funds and insurance company ownership falling from 45.7% in 1997 to 4.2% in 2022.

The culprits for decline

The massive sell-off among UK institutions is generally attributed to the introduction of a new accounting standard in 2000 (FRS17) that required companies to calculate the surplus or deficit of pensions each year and disclose these in the financial statements. Rather than subject their financial results to pension-induced volatility, most companies (aided extensively by UK investment consultants) adopted asset liability matching in their investment portfolio, which in practice meant selling equities and buying bonds, with some illiquid private funds thrown in too.

FRS17 wasn’t the only culprit though. Over the period investors in general took a more global approach and shifted from public to private markets. And the UK’s importance to the global economy declined on a relative basis as China and others rose. But the combined effect was to remove UK institutions as a major investor in the UK stock market, which when added to stagnant levels of retail ownership, has left the market lacking a strong domestic investor base.

In theory that shouldn’t matter, who cares where the money comes from? In practice, overseas investors tend to focus on larger cap names, have less interest in domestic companies, and have tighter restrictions on liquidity. All this has created a rather unvirtuous circle in which poor performance and little domestic interest begets a reliance on overseas investors and a focus on larger cap names, which further reduces liquidity among smaller and medium-sized firms.

In this state there is a genuine question as to whether the stock market is best serving what should be one of its primary goals – raising capital for growing UK businesses and reallocating capital from mature to emerging firms.

Reforms on the horizon

The good news is that none of this has gone unnoticed and there has been a flurry of reforms announced in recent years, many of which seem sensible, some of which seem a bit ‘meh’, but all of which suggest a brighter future ahead. These include:

Overhaul of the UK listings regime with key changes including that firms will not be required to consult their shareholders on certain deals and will be allowed to use long-term dual-class share structures. Some pension funds have kicked up a fuss, concerned that this will dilute the UK’s reputation as a beacon of corporate governance. Yet these same funds happily invest in Meta and Berkshire Hathaway, whose dual class share structures have so clearly destroyed shareholder value… The fact is dual class share structures are where the market is at and the UK is rightly adapting to it.

Prospectus reforms and a secondary capital raising review, both of which are looking at reforms to make it easier for firms to list in the UK and to raise additional capital once listed.

Investment research review recommending greater flexibility in paying for research and more access to research for retail investors (all seems sensible) with the establishment of a new, central research platform for retail investors (of which I’m highly sceptical, given the high chance it takes years to deliver and contains only overly hedged, mediocre content). But also in the report is a recommendation to build out the FCA’s National Storage Mechanism to create a central repository of company reports equivalent to the SEC’s EDGAR. That could be the key value of any central platform and should be the easiest to deliver too.

Proposal for a new British ISA in which UK savers would get a £5,000 allowance to invest in UK shares tax-free (no income tax on dividends, no capital gains on sale). This has met with a mixed reception, criticised for being too gimmicky or too small to be of use. A more positive take is that it’s a first step in reviving retail interest in domestic stocks, at what’s likely a low cost to the UK taxpayer.

Reforms to get UK DC pension funds to target 5% investment in private assets (including shares on AIM and Acquis) are, well, just targets. Even if they weren’t any 5% allocation could quickly be gobbled up by large , global buyout funds. But much like the British ISA, the positive take is that this is a step in the direction of nudging more of the UK’s domestic savings to be invested in UK companies.

New exchange to allow secondary trading of shares in private companies on an intermittent basis, with the goal of helping businesses grow by providing liquidity to early shareholders without needing to access public markets. Sounds okay, but in practice liquidity is available for private holdings today (it’s just over-the-counter vs. on an exchange). Interesting to see where the responses to the recent consultation on this end up.

There’s a lot of activity here and it’s difficult to say in advance what will or won’t work. What’s notably lacking is an absence of any major changes to the taxation of equity investment or share trading in the UK. But what gives me hope is that there is an emerging political consensus over the importance of the UK equity market and a concerted effort to make the market competitive today.

That doesn’t solve for the problem of creating good companies, which is fundamentally what will drive performance in the long run, and good performance will drive more investment. But it could help in the short to medium term by supporting a flow of money into UK stocks. Add in some other reasons for optimism, such as the positive case for the UK economy, and the simple fact that some really unhelpful things have stopped happening (i.e. UK pension funds have no more UK stocks left to sell) and there is a case for a UK equity revival that doesn’t solely rest on “it’s so cheap” and “things can only get better from here”.

More to follow in future weeks on the themes here!

Thanks for this interesting read. I do wonder if the value of reducing or removing stamp duty that some have called for. Is this simply self serving or aligned to your take on many small nudges to push the ship (my words)?