The Americans Are Coming: A Deep Dive on UK Investment Trusts

Why I'm siding with the Americans on this one

This is not investment advice. It is my opinion only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any stock or investment product. You should do your own research and invest according to your own financial circumstances.

If you’ve been following the UK investment industry, you’ll have seen the headlines around Saba Capital’s attempt to take control of seven UK investment trusts. The US hedge fund lost the opening round of its figastht l week, after shareholders in Herald Investment Trust voted resoundingly against Saba’s plans. Further votes will take place this week, but if Herald is anything to go by - 99.78% of non-Saba shareholders voted against – then the UK trust industry will be patting itself on the back for successfully fending off the American attack.

Having come from a US-based investment background – working for US firms, marketing US funds – I’m still learning about some of the quirks of the UK investment world. And instinctively, I’ve never liked investment trusts, or what Americans call closed-end funds. I can’t understand why they’re included in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250, and I don’t understand the value of holding listed equities in a closed-end structure. Why not just buy a mutual fund? Or an ETF? There’s a good case for using these funds to invest in illiquid assets but my cynical self says this is also just an opportunity for mediocre managers to charge high fees.

So, I’ve been digging into this world of investment trusts to understand what’s been going on, and whether my instincts to side with the Americans are correct. This is a long one and I want to start with some history. If you feel confident in your understanding of discounts to NAV, jump ahead to views on Saba.

History of UK investment trusts

The first UK investment trust, Foreign & Colonial Investment Trust, was launched in 1868. It still exists today, although the British empire does not, and hence it goes by the name F&C. F&C is a FTSE 100 listed company with assets of over £6 billion. It’s benchmarked to the FTSE All World Index and holds shares in over 350 companies in 35 countries with ongoing charges of 0.49% per year. It’s a broad, global equity portfolio then, the likes of which you could buy as a passive ETF at half the cost.

But 156 years ago, that option wasn’t available. Neither were mutual funds (or open-ended investment companies or unit trusts, as the equivalent structures are often called in the UK). Investment trusts offered the chance to invest in a diversified portfolio – initially of government bonds, then American railroads and the like, finally an array of global assets.

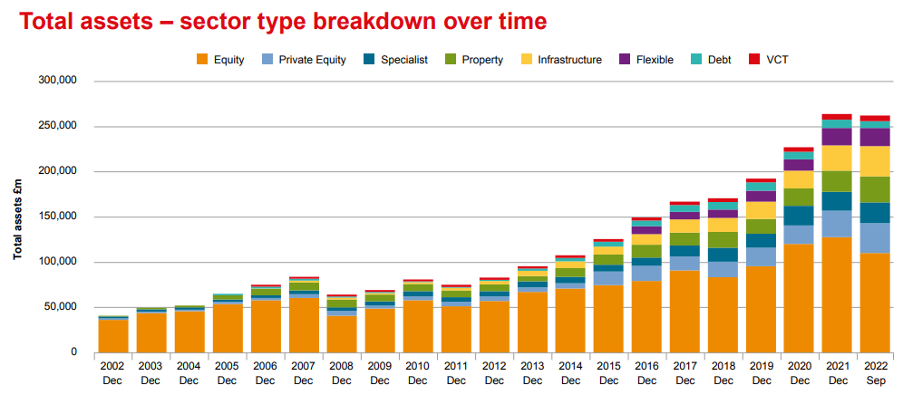

Today, investment trusts are dwarfed in size by mutual funds, but perhaps because they originated in the UK, were the only game in town for many years, and because UK mutual funds were littered with expensive fees for a long time, investment trusts in the UK still play an outsized role in the industry relative to other countries. As of December 2024, there was £268bn invested in UK listed trusts versus £1,529bn in UK funds, meaning investment trusts held 15% of total UK-domiciled assets. In comparison, closed-end funds in the US (the closest equivalent) held only 3% of total fund assets.1

How investment trusts work

That’s a lot of talk about trusts and mutual funds, and open-end and closed-end. What does it all mean?

The key structural feature of an investment trust (closed-end fund) is that they are listed companies that trade on an exchange like any other stock, and whose price goes up and down throughout the course of the trading day, just like any other stock.

The difference between a trust and any other stock is that the trust operates only to manage the funds it has raised, and its assets are the investments it makes (which could be in equities, bonds, private equity, infrastructure etc.).

The difference between a trust and a mutual fund (open-ended funds) is that a trust raises money by issuing a fixed number of shares, and investors then buy and sell the shares through the stock exchange. The trust does not need to manage inflows and outflows; it just invests the money it raises at the start and gets on with it.

In contrast, a mutual fund issues new shares every time an investor buys in and redeems shares when they sell out. The mutual fund manages these inflows and outflows by buying and selling underlying assets.

This structural difference gives rise to three main features of investment trusts aka closed-end funds:

They can use borrowing (aka gearing), because they are legally structured as companies, and because they have a stable capital base.

They can invest in illiquid assets, because if you don’t have to worry about managing inflows and outflows, you don’t have to worry about holding assets that are hard to buy and sell.

They can trade at a different price to the underlying Net Asset Value (NAV) of the investments they hold, because they have a fixed number of shares and the share price will reflect demand and supply for the trust, as well as the underlying value of the assets it invests in.

That final feature – the difference between the NAV and the share price – is what brings us back to the Saba Capital battle today, because Saba’s main criticism is that UK investment trusts have allowed large discounts to NAV to persist. And that the boards of the investment trusts have been negligent in their duty to shareholders to try and close the discounts.

Persistent discounts to NAV: A fair criticism?

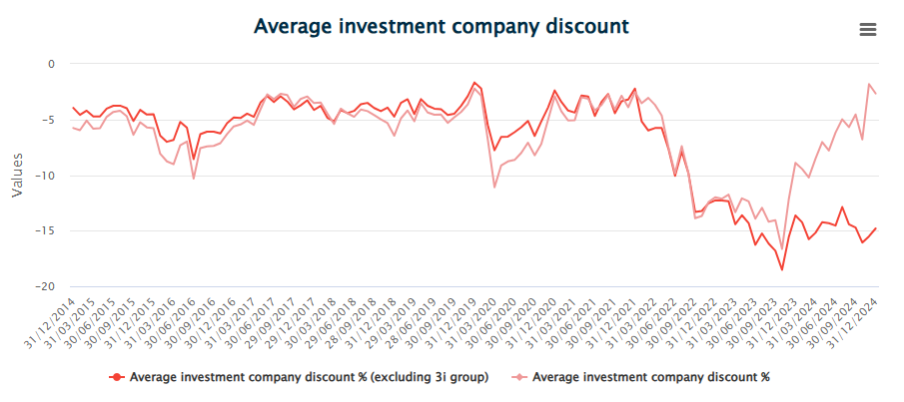

Discounts to NAV are an evergreen feature of investment trusts, averaging about 5% between 2014 and 2021 based on this chart from the Association of Investment Companies.

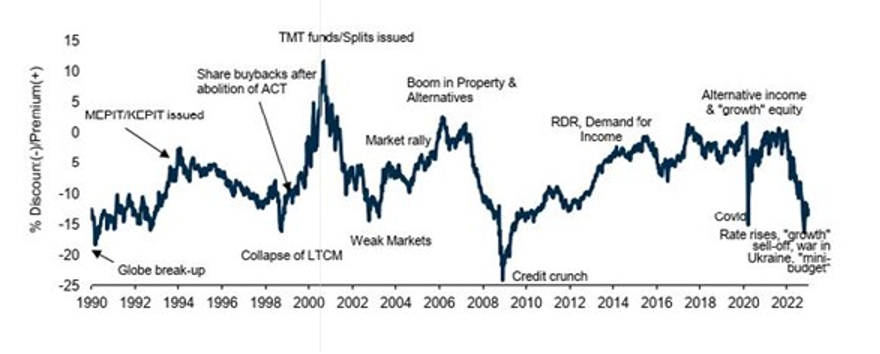

Going back even further (in blurry form courtesy of an old Schroders article via EQI via Google…) there’s been a few periods of exuberant demand for investment trusts. Trusts traded close to NAV in the early 2000s (which ended in a big scandal around split trusts2), in the immediate years before the GFC (because property prices only go up!), and in the 2010s zero interest rate policy era (because the leverage in trusts could enhance yields). But there’s also been plenty of other periods when trusts traded at large discounts: in the early 1990s, in the mid-2000s, and in the years after the GFC.

In a textbook view of the world, assuming no transaction costs, perfect information, etc., etc., there would be no difference between the NAV and the share price of the trust. If the share price trades below NAV, a trader could buy the fund, while selling short the underlying assets, to lock in a risk-free profit. Seeing a risk-free trade, capital will flow to the opportunity, and increasing demand for the fund will push up the share price. Arbitrageurs will close the discount.

Now nothing ever works like it does in the textbook, and there’s plenty of reasons for discounts to persist:

The NAV isn’t accurate: If the funds invest in publicly listed equities, then pricing the underlying assets isn’t hard, you just use the closing price of the shares and disclose it daily. But if they invest in private assets, as many increasingly do, there is no daily price. Instead, there is normally a quarterly valuation process – not quite finger in the air, but full of assumptions and uncertainty. If public markets tank and the trust has an NAV based off valuations done three months ago, then the discount will substantially widen as investors quite rightly say, we don’t believe that NAV anymore.

Transaction costs are not zero: In the arbitrage example above you need to construct a portfolio that shorts the underlying assets. With large cap liquid stocks, professional traders can do this, but with private and small cap names it’s going to get tricky quickly. A simpler way to make the same trade for the benefit of existing shareholders is for the board to wind up the fund - sell all the assets, return the cash. Or a third party could buy the whole fund, which is what the British Coal Pension Fund did in 1990 when they succeeded with a hostile takeover of Globe Investment Trust, at the time the largest in the UK. A less extreme option for boards is to buy back shares, which is equivalent to selling selling (the underlying assets) high and buying (the shares) low.

Incentives aren’t always aligned: To buy back shares or wind up the fund you need board approval, and often there isn’t much incentive for the board to provide this. Large buybacks mean selling assets, which lowers the assets under management (AUM). Fees are typically charged as a percentage of AUM so a vote for buybacks is a vote for lower fees (at least in the short term). Boards should of course be independent of the management company and not concerned by fees, but in practice it’s never quite so black and white. And a vote to wind-up a trust is a vote to wind-up a nice non-executive position. Turkeys voting for Christmas and all that. Because of this, criticism of investment trust boards has been longstanding, way before Saba got involved. In fact, in 2023 there was a big bust up at Scottish Mortgage Trust.

Why have discounts widened since 2021?

Well, if you believe the former Pensions Minister, it’s the fault of the EU!

“The leftover EU rules were definitely part of the reason Saba was able to swoop in and take advantage of the excessive discounts that resulted, at least in part, from misleading charge figures forced on trusts by misapplied regulations,” Altmann told the Mail.

Leaving aside the fact that the fee disclosure rules came in in 2018, and the UK fully left the EU in 2019, I tend to think something more important happened between 2021 and 2023.

Interest rates started rising, rapidly. The UK 10-year gilt went from 0.85% in January 2020 to 3.5% at the end of 2023.

At the same time, the investment trust world had become increasingly exposed to private assets, in the form of private equity, property and infrastructure, all of which have significant interest rate risk.

Private equity utilises a lot of borrowing and has experienced well publicised issues with realising investments in recent years. Infrastructure has been sold as a long-term stream of income, much like a bond. And if yields go up, bond prices go down. Failing to acknowledge this - or just hoping that rates will fall, and you can wait out lower valuations - has I imagine been widespread.

The industry will say there are a lot of factors at play, but the widening in discounts that started in 2021 seems to me a pretty clear-cut case of the market saying, no, we don’t believe your valuations.

And in some cases, the market has been proved correct. Digital 9 has been the poster child of poor governance and poor asset management. The infrastructure trust launched in 2021, but the board voted to wind it up in 2024 following funding problems in 2023 (yes, higher interest rates).

After starting the process of selling assets, it became clear they couldn’t get anywhere close to book value. In September 2024 Digital 9 estimated a ~40% cut in valuations from those reported at the end of 2023 and it’s got worse since:

“The 80 per cent discounts that Digital 9 has previously traded at suggest that the market got this about right,” added Quoteddata analyst Matthew Read.

A closer look at Saba’s plans

Now not all investment trusts are alike, and while the above explains the discounts on illiquid investment strategies, and the failures of boards to act to close them (because the assets aren’t actually undervalued), it doesn’t make sense for those that invest in liquid securities (because we know daily what the price of those are).

That’s where we get into more “woolly” explanations for persistent discounts, along the lines of there’s not enough demand because the EU rules on fees are putting investors off, or because public investment strategies have been tarred with the same brush as private ones, or because performance has been poor and its putting buyers off. And sure, those all explain why there may be a discount, but they don’t explain why boards aren’t doing more to close it, because again, if the trust invests in listed securities and has confidence in what the NAV is, then there is value to shareholders from buying back shares or winding up the fund. Simply put, demand for investment trust shares has fallen, supply should too.

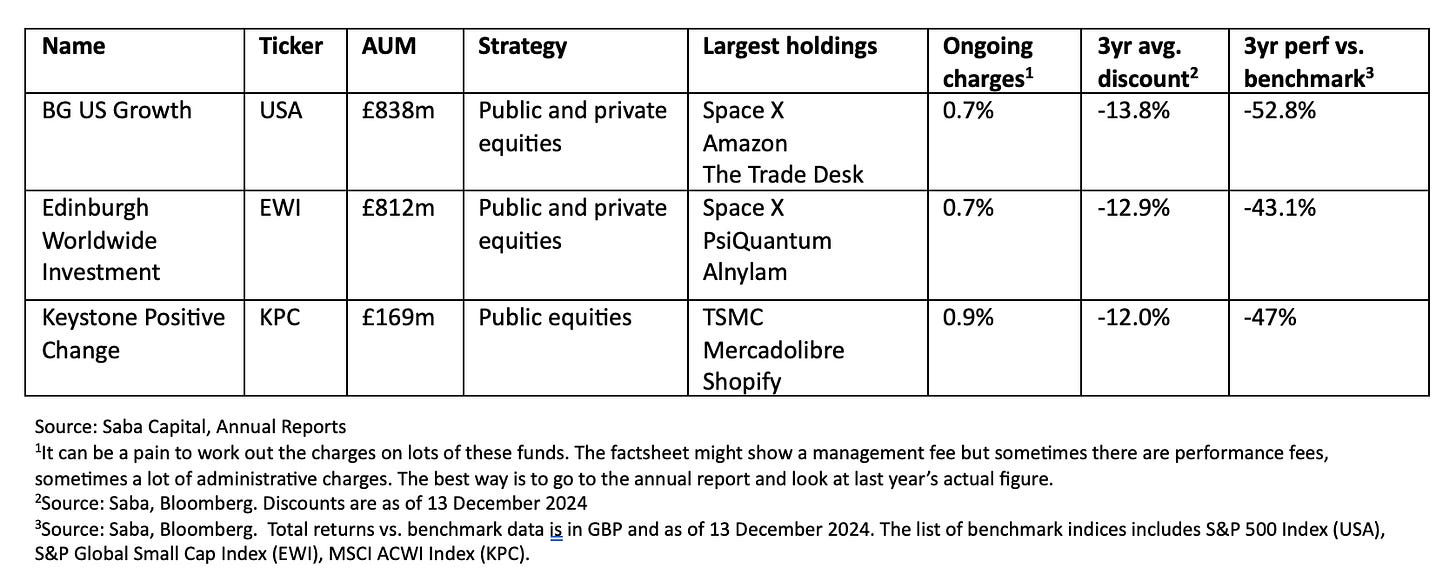

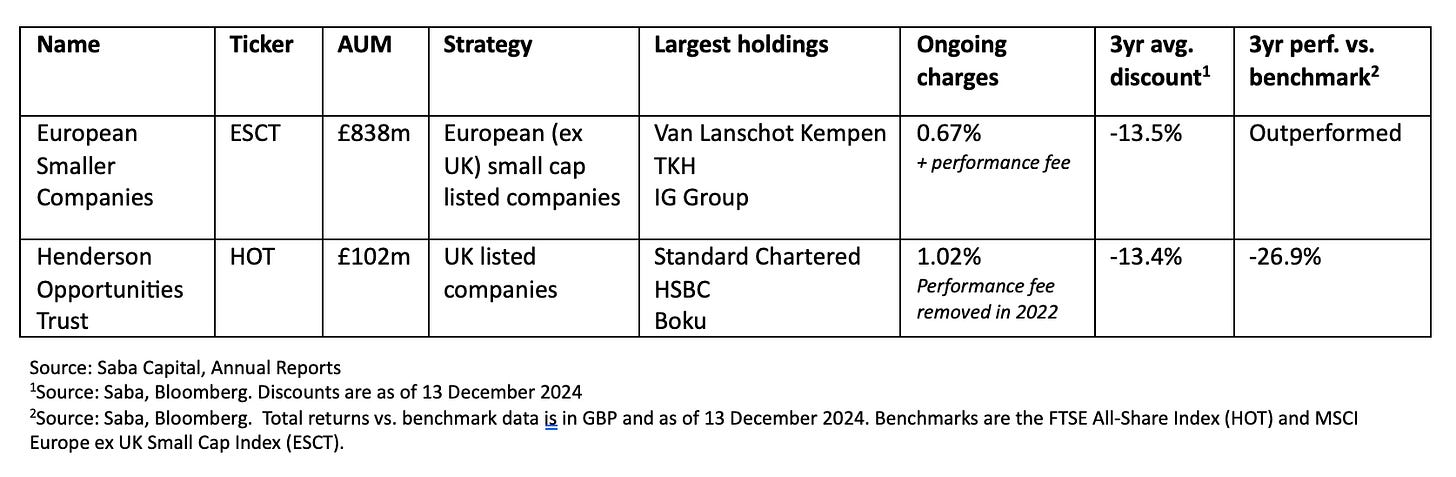

It's no surprise then that the seven trusts Saba has targeted invest mainly in liquid securities. Let’s look at these in more detail.

Baillie Gifford managed trusts

Saba argues that these funds have underperformed their benchmarks over the last three years, with persistent discounts to NAV that only closed due to Saba buying shares. Looking at the figures this seems a fair criticism – although how bad it is versus other trusts I don’t know. There does however seem to be a clear case for consolidation, given the similarity in strategy between USA and EWI, and the small size of KPC (which was looking at winding-up even before Saba’s approach).

Because of its small size, KPC’s ongoing charges are high, and the board cited this as an argument against buybacks i.e. by reducing the share count, it increases charges for remaining shareholders. Except I don’t think that’s an argument against buybacks, but rather an admission that the fund is sub-scale and needs to be wound-up.

So, while Saba hasn’t given much detail on its plans, some sort of consolidation feels eminently sensible. Merge funds, sell assets, market the hell out of giving retail investors the chance to own some of Space X (which as much as I hate Musk, still sounds exciting).

Janus Henderson managed trusts

The Janus Henderson funds are similar to Baillie Gifford in there being one fund that looks subscale, too expensive, and underperforming (HOT). The other fund (ESCT) is unique among Saba’s targets in outperforming the benchmark over the last three years, not that that’s helped its NAV discount. The bigger issue for me with ESCT is the presence of a performance fee that isn’t easy to dig out the details on (again, go to the annual report), and which will materially eat into total returns e.g., in 2023 the performance fee was twice the level of the management fee.

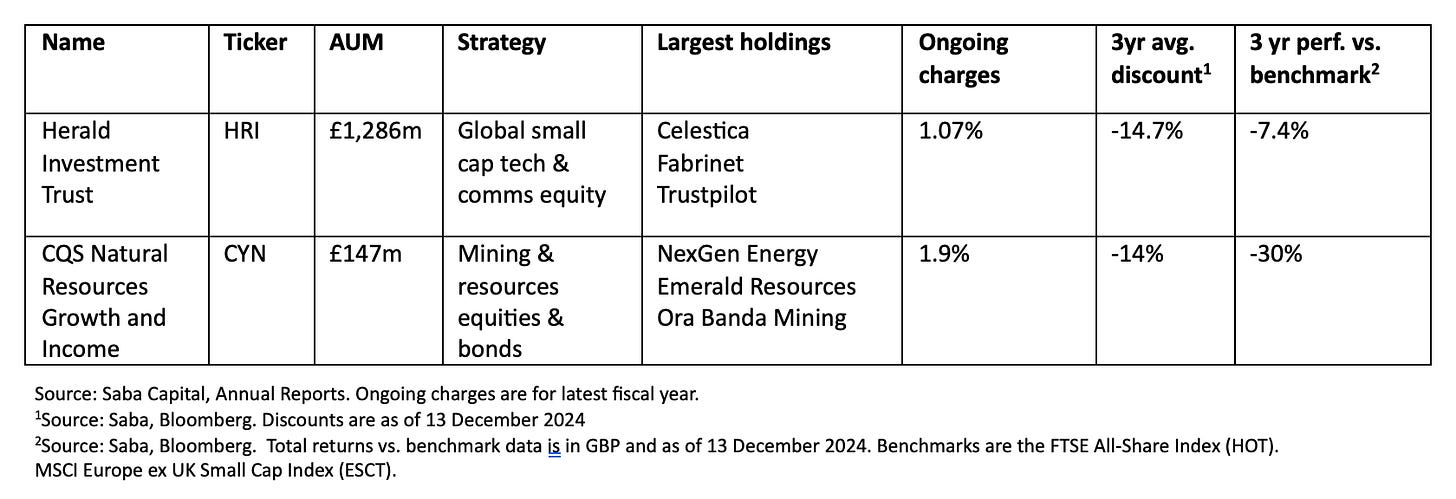

Herald and CQS/Manulife managed trusts

The final basket of funds includes Herald (HRI), the only trust to have held a vote on Saba’s proposals, whose shareholders overwhelmingly rejected them, and CQS Natural Resources (CYN), which is a relic of the commodity super-cycle of the early 2000s. HRI is the largest target on the hitlist and despite performance being okay-ish, Saba argues that it has failed to take actions to remedy the discount to NAV. CQS has had both poor performance and a large discount; and with a 1.9% fee is the priciest strategy on this list.

The short summary is I wouldn’t invest in any of these funds but that’s true of many actively managed one, whether open or closed-end.

The British backlash

For an industry often described as “cosy” and “sleepy”, it’s been an impressive rearguard action, helped along by the British tabloid press. Platforms have been pressured into ensuring shareholders can easily vote (a good thing in general), and the narrative has leaned heavily on the American vulture fund versus the dogged resistance of individual investors

The more specific arguments against Saba fall into the following buckets:

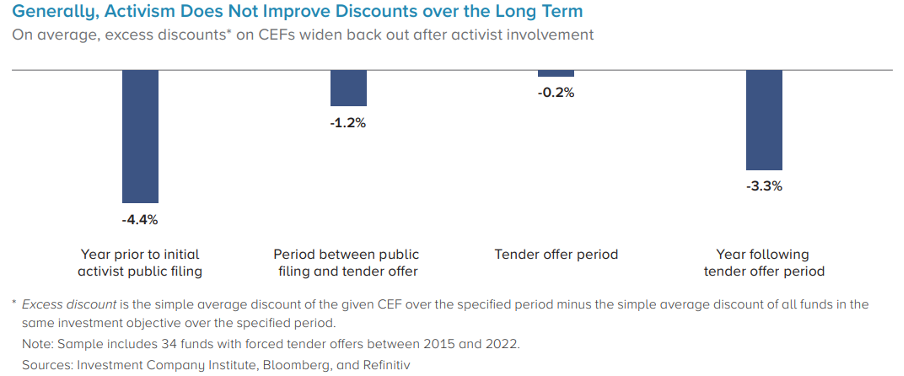

Saba will destroy value in the long-term, which leans heavily on the performance of Saba’s ETFs in the US and evidence from the US that activist investors have not improved the discounts on funds over the long-term. Research from the Investment Company Institute does support this – but then no one is being forced to stick around for the long-term.

Saba is only in it for short-term gain, which is similar to the first point. Saba has been honest that it will make significantly more by closing the discount to NAV and taking the gain on its shareholding, rather than benefitting from management fees in the long-term. But I don’t see how this is to the detriment of other shareholders who will also benefit from that gain – and who are being offered the chance to cash out at close to NAV.

Saba could radically alter the investment mandates and deprive investors of exposure to the current strategies, which is perfectly possible but not an argument to vote against. If there’s demand for these types of products, others will take their place.

Saba’s actions will deprive UK companies of capital, which is nonsense, because most of these funds invest primarily in overseas companies (and c.45% of total assets in the investment trust industry is invested overseas), and the one UK-only strategy (HOT) has assets of £102m, which is utterly piddly in the great scheme of capital availability.

Siding with the Americans

Boaz Weinstein has come in for a lot of heat but the interesting thing for me is we’ve been here before:

“Scorched earth with a cynical twist couched in a litany of highly selective statistics"

That’s how the Chairman of Perpetual Income and Growth Trust described Securities Trust of Scotland, as it rejected its takeover bid in 2005. This was at a time when:

Shares in the sector have been constantly trading at a discount to the net asset value of their underlying portfolios, while the recent trauma of split capital trusts[1] has dented the sector's reputation, which hitherto enjoyed an untarnished record for generations.

The battle for STS is the latest sign of a growing appetite for action among the more forward-thinking trust boards rather than the sector's traditional supine attitude to change.

At the end of the day, if shareholders want to stick with these trusts, that is their right. Saba is proposing to replace the entire boards, replace the investment managers, and change the investment mandates. So this is a wind-up of the trusts in their current form. In return for voting for this, shareholders can take up the option of a “liquidity event” (tenders and buybacks) to sell their shares at close to NAV, although the exact details of this have not been provided.

Given the PR campaign, and the sense of being attacked by a New York hedge fund, I’d be surprised if Saba wins the votes. Individuals will also have their own circumstances to consider, based on the levels they bought in and tax liabilities, etc. And it feels like a step into the unknown if your goal was to just buy a trust and let it be.

But if history is to go by, the investment trust world needs a periodic shake up, and Saba deserves credit for initiating it this time round. These trusts aren’t helpless victims of an attack. The boards - and the management companies - were asleep at the wheel and left themselves vulnerable to it.

Source: Association of Investment Companies, Investment Association, Investment Company Institute, FRED. UK trust AUM is as of 31 December 2024. UK mutual fund AUM is as of November 2024. US figures are as of December 2023.

I’d never heard of this one before, but in the 2000s, the industry started offering “Split capital trusts”. These were investment trusts with two different types of shares. One class received all dividend income on the investment, and another benefited solely from rises in the capital value of investments. Split capitals were widely marketed as safe investments but came under severe pressure after the dot com crash and people lost a lot of money.

I really enjoyed reading this although on balance I side with the British. I invest in a couple of ITs, where the closed end structure makes sense due to illiquid assets such as private companies and PE. I think the days of

IT trying to just have publicly listed assets is getting passé in an era of ETFs but I was pretty unimpressed by Saba proposals. They had no real way forward and the play to replace boards and award themselves the asset management was unconvincing. I do think though they’ve provided the IT boards the necessary kick up the backside. Be interesting to see how they get on this week.

Very good article - Thanks for taking the time and for sharing, appreciated.