Councils, Carry Trades and Commercial Property

How UK local authorities commercial property portfolios are holding up

This is another topic I’m recycling from a blog written six years ago. Back then I wrote about local authorities in the UK buying commercial property – what could go wrong?! Well, collapsing commercial property values for one. To be fair to local authorities, there was unlimited, cheap debt available, and they were trying to manage large cuts to operating budgets with rising demand for services. With more details recently emerging around Thurrock council’s adventures in solar farms, I thought it would be interesting to check in on how other commercial investment portfolios are working out.

A quick recap

For those outside the UK, and for others not familiar, let’s start with a quick recap of the situation six years ago, when there was a flurry of media interest in UK local authorities building up commercial property investment portfolios. Spelthorne Borough Council became the poster child for this in 2017 when it paid £358 million for a sprawling BP campus in London’s western suburbs. A few purchases later and Spelthorne, with an annual budget of £22m, had amassed a portfolio of office buildings valued at close to £1 billion.

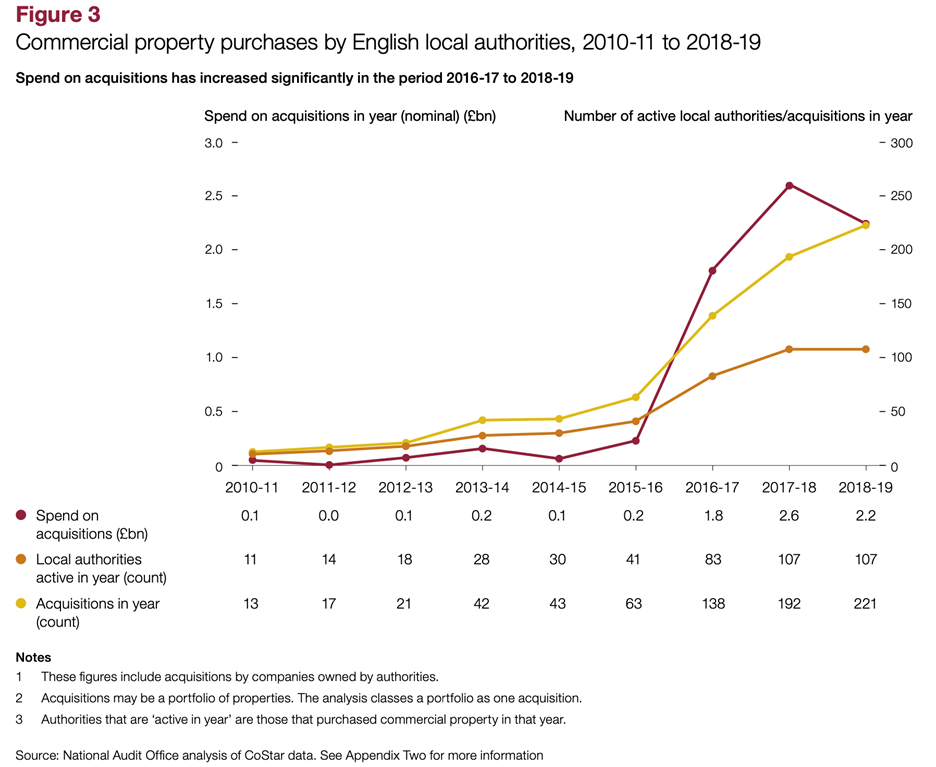

Local authorities had long made investments in commercial property, but the 2016/17 to 2018/19 period was altogether different. The NAO estimated that local authorities spent £6.6 billion on commercial property during these three years, 14.4 times more than in the preceding three-year period. In the South East, 17.5% of all commercial property acquisitions by value during these years were made by local authorities.1

Historically commercial property investments were tied to local areas, often with local policy objectives. The shift in 2016 was that it became a pure investment, a means of generating income for cash-strapped councils.

The financial and legal basis for amassing commercial property portfolios was questionable from the start, and it was a small number of authorities that accounted for most of the investing. According to the NAO, 80% of the cumulative spend over the period 2016/17 to 2018/19 came from 13.9% of local authorities. Among them the big players were Woking, Spelthorne, Thurrock, Runnymede, Warrington and Eastleigh – mostly small areas in the South East.

Where did the money come from?

The great PWLB carry trade

UK local authorities receive funds from council tax and business rates plus grants from central government and revenues from any paid services. In the name of austerity, government grants fell by 40% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2019/20, forcing councils to cut services or seek new revenue sources.

Since councils were limited in raising taxes and renting out the leisure center only goes so far, they became more creative in finding funding sources. Enter the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB), an entity within the government’s Debt Management Office that provides loans to local authorities (effectively funded by gilts). The loans were intended to finance capital projects; and the Treasury had limited powers over their use prior to 2020.

How it worked

The PWLB lent money to the local authority with little scrutiny over what the money was used for, at a similar rate to the UK government’s cost of borrowing. There was little scrutiny because local authorities were responsible for their own financial decision making, subject to complying with a Prudential Code that proved loose and vague in practice.

The council took the borrowed funds and bought office buildings or shopping malls or solar farms, with the rental income from the investments used to pay back the loans and manage the property. Anything left over was used to fund local services.

Ian Harvey, the leader of Spelthorne Borough Council at the time, recalled the process of lending from the PWLB:

“I found it laughably easy, to be honest with you,” he said. “There was no real control over it. I’m told it was pretty much a phone call. It took about three days.”

In investment terms, this is a carry trade. Borrow at a low interest rate, invest the money in an asset that pays a higher interest rate, pocket the difference. Sounds simple enough but it can easily go wrong.

What could go wrong?

It didn’t take much to foresee some major risks down the line.

First, that lease payments could fall in an economic downturn or as existing leases were renewed. Spelthorne makes much of its high-quality tenants, but its portfolio is highly concentrated with over £18m in revenues coming from BP. And while I’m confident in BP’s credit over the next 14 years, I’m not confident that BP will continue to lease the building after that, when its current lease expires. Even if it does, Spelthorne is going to be over a barrel in renegotiating new terms.

Second, that office buildings normally require significant capital investment between tenants to keep the facilities up to date; otherwise, the building deteriorates, and rental incomes are lower than they might be. Over a 50-year holding period this includes a full electrical and mechanical refit. Active management and financial planning are critical to build up reserves to cover these future refurbishments.

Finally, it was blindingly obvious that local authorities were likely being taken for a ride by private advisors and investors. The PWLB’s cheap cost of funds (well below commercial funding costs) could enable councils to outbid private investors; the council’s own lack of experience could lead it to accept lower returns and misprice risks.

What’s happened since?

Well the UK government was not blind to this, and did indeed clamp down on the use of the PWLB, increasing the cost of new loans by 1 percentage point in 2019, and in November 2020 introducing new lending terms that banned local authorities from using PWLB funds to purchase assets purely for yield. This stopped the commercial property portfolios growing further but didn’t change the investments already made.

As for those investments, many of the risks have been validated – even if it’s not been quite the disaster foreseen.

A damning report

KPMG was the auditor to Spelthorne and when I looked at this in 2019, had still not signed off on the 2017-18 accounts. In November 2022, KPMG issued a public interest report on the accounts in which they claim Spelthorne acted unlawfully as it did not have appropriate powers to borrow and purchase three specific buildings in the circumstances in which it did.

Spelthorne deny this, the government has subsequently changed guidance to clarify the position, and I’m no legal expert. But whether it was lawful or not, the report is damning on Spelthorne’s investment process and sophistication:2

The financial models that were developed by the Council are simplistic in nature and do not follow industry best practice.

The Council’s predicted internal rate of return on the investment property portfolio is, in our view, well below the level that an institutional investor would expect to achieve.

There is a risk that the modelled rental income may be overestimated, and potential costs have been understated.

The lack of sophistication in the Council’s financial models has, in our view, created a disconnect between the lease lengths (up to 20 years) and the loans (50 years).

The structure of the Council’s transactions, i.e., on the balance sheet as opposed to the debt being secured against the Properties, means that Council would be liable for the debt payment irrespective of the performance and value of the assets.

To be fair to Spelthorne, the portfolio hasn’t been a complete trainwreck, yet. The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) noted in its Capital Assurance Review for Spelthorne that the council managed through the pandemic, meeting all obligations and paying money into a sinking fund (set up to manage fluctuations in rental income and build reserves for future refits and refurbishment). The council had a strong track-record on rent collection and its commercial portfolio was contributing around £10m per annum to net revenues (i.e. post borrowing costs and sinking fund provisions).3

Falling valuations

But at the end of 2023, its commercial investment portfolio was valued at 24% below purchase price. Despite some recovery in commercial real estate prices since then, it’s hard to see these peripheral London assets benefitting most in a market where prime, central locations are key.

The purchases were funded 100% by loans from the PWLB, and in any normal world a 24% loss on a 100% leveraged portfolio would be a complete disaster. You can counter here that the PWLB debt is not secured on the properties and there are no margin calls against the fluctuating value of investments. So, if Spelthorne has the income to service the debt, there’s not a problem. However, any shortfalls in income, and valuations soon catch up with you if selling the buildings is the only way to pay back the borrowing.

In 2023 CIPFA reported that the council had an expected income shortfall of £10 million over the next two years due to the loss of key tenants, requiring Spelthorne to draw on its sinking fund. Given the fund was only £33 million at 31 March 2022, it won’t last long should this shortfall persist. Charter Building, the office block in Uxbridge, looks only c.50% occupied from its website, which doesn’t bode well.

So, while Spelthorne is hanging on, avoiding a Section 114 notice that is equivalent to a local authority bankruptcy, it is also now subject to an outside inspector after a CIPFA assessment concluded that:4

The portfolio of debt-funded investments for Spelthorne Borough Council was very large and that there were serious financial concerns relating to the Council’s affordable housing plans. Considering the review’s findings, together with the Council’s response and other related assessments, ministers have taken the view that there are clear financial risks, and, if they materialise, that are likely to have significant impact on local residents and some impact on the national public purse.

Trainwrecks elsewhere

The same can’t be said for other local authorities.

Woking Borough Council is a similar size and has a similar budget to Spelthorne, and yet managed to run up borrowing more than twice as large - £1.9 billon, rising to £2.4 billion, with interest costs of £62m per year against an annual council tax take of £11m. The borrowing was mostly in relation to two major redevelopment projects in its town centre that it has since written down by c.£600m.

Thurrock Council, east of London, took a different approach, eschewing office blocks but going all in on solar farms courtesy of about £1.4bn of borrowing, some of which was funneled off to fund luxury lifestyles in Dubai. The investments were duds, and the council was forced to sell its portfolio for close to £700m, having issued a Section 114 notice at the end of 2022.

That said, the biggest local authority failure to date, Birmingham City Council, has admittedly had nothing to do with commercial property or renewable energy investing. Instead, it seems a result of gross mismanagement, a disastrous rollout of a new IT system and liabilities from claims over equal pay.

What to make of all this?

Despite working in government, I’m still unclear why central government didn’t step in sooner to stop some of this activity. My best guess is that the fires weren’t burning while others were, and they fell down a long list of priorities, bogged down by legal considerations and a lack of powers for HM Treasury to stop it directly (since amended). I suppose the horse had also already bolted in terms of the 2016-2019 spending spree too.

More broadly this is a symptom of the dysfunction in local government funding in the UK, where demand for local services (e.g., social care) continues to rise while funds available fall (although this has stabilised post 2020). So far, we’ve seen little from the new government on their plans for this.

It’s also a reminder of the UK’s unfortunate habit of cutting costs in the short run to store up trouble in the long run while hollowing out public sector expertise. The Audit Commission was a body set up in 1982 with the primary objective of appointing auditors to local public bodies and setting standards for their work. In 2010 the Conservative government decided to save £50m a year (in theory) and shut down the Commission, which closed in 2015. Its oversight function was instead to be covered through private sector audits and a new Prudential Framework for spending – this hasn’t worked out so well.

Finally, it’s a reminder that the UK did have money to spend, we just chose to spend it badly. £6.6 billion isn’t much in the great government budget but there were better uses for it than buying office blocks.

On a different note…

I’ve been out of action for the last month caught up in unpacking 300+ boxes and starting new routines in a new country. But I’m pretty much settled here in the US and plan to start a longer-term project, moving away from griping about past governments (although I’m sure I’ll return to it), and looking more optimistically at investment opportunities in the UK. I’ll start next week with a tour through the FTSE 250.

Great article, if a little alarming. Now you're in the US it'd be interesting to look into Municipal Bonds ('Munis') as a comparator in raising money locally.