Building a UK Equity Portfolio: Part 2

Thoughts on investment universe, style, process and portfolio construction

Last week’s post tackled the question of why bother picking stocks at all. This week, I’m going into more detail on my process for doing so. If you missed last week, you can start here:

My experience with professional asset management was that an investment approach that looked streamlined, methodical and consistent on paper, was always messier in practice. Investment styles could drift. Losing positions could linger. Risk management could fall by the wayside. But that doesn’t mean you want a blank sheet of paper instead.

It’s important to have some guiding principles – otherwise how are you going to wade through the thousands of listed companies out there? Broadly these fall into the following buckets:

Universe – where are you going to pick your stocks from?

Style – what type of company do you want to invest in?

Process – how are you going to find those firms?

Portfolio construction – how many companies to hold and for how long?

Risk management – how can you protect against complete disaster?

If you’re a professional, you’ll spend hundreds of pages detailing the above in an RFP for any investment mandate. But I’m not a professional, although I have written and read my fair share of RFPs. They’re mind-numbingly dull and largely sound the same. I’m going to keep things simple.

Investment universe

First up is an easy one. I’m going to limit myself to companies in the FTSE 250 index, excluding investment trusts. I don’t like investment trusts because if I’m going to outsource money management, I’d rather have a low-cost passive fund then some quirky active mandate with hidden fees.

I’m focusing on the FTSE 250 because this is a Substack about the UK, designed to showcase UK investment opportunities; the FTSE 250 contains mid-cap companies that are lesser known, particularly to an international audience; and the index itself has been trading at a discount to historic valuations suggesting there’s opportunities in there. There’s around 160 non-investment trust companies in the FTSE 250, which also seems like a reasonable number to have a cursory knowledge of as a one-man band.

Investment style

With the universe set, the next part is to determine what type of companies make the cut. One way to do this is to ask what characteristics have driven returns in the past. Which leads me to the Fama-French three factor model and the Morningstar style box that emerged alongside it.

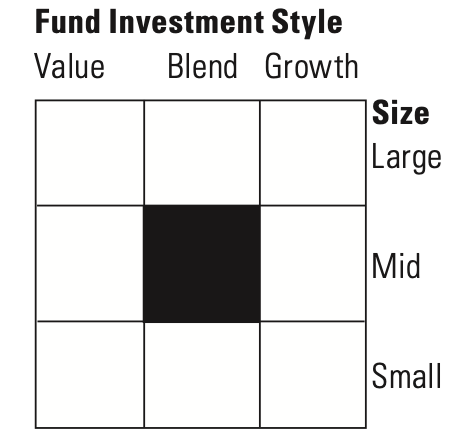

The style box was launched in 1992, the same year that Fama and French published a paper on stock market returns.1 It places an investment strategy in a 3x3 matrix based on the characteristics of firms targeted (value vs growth) and size (large-cap vs small-cap).

The style box was consistent with Fama and French’s research that showed stock returns could be explained by the overall market return, the market cap of the company and whether it was growth or value. They found that historically small cap stocks outperformed large cap stocks, and firms with low valuations outperformed those with high valuations, as measured by price-to-book ratio.

Fama and French went on to refine their work – finding that “quality” companies with higher profitability and higher levels of investment also outperformed. Separately, momentum (in which stocks that have gone up in the past continue to do so) and low volatility (stocks that have lower volatility than the market) were also identified as “factors” that could explain stock returns. But a 5x5, or a 6x6, is far too complicated, so the 3x3 remained.2

At first glance it’s tempting to say let’s have a small-cap value investment style, that seems to work! But as with a lot of financial data, it’s heavily time-period dependent. What worked in one period, under one set of economic conditions, doesn’t work in another. And so it is that in broad terms, small-cap value investors got hosed over the last decade, because during this time you would have been best owning large-cap technology stocks in the US, despite many trading at what seemed like eye-wateringly high valuations at the time.

All this leads me to believe that being laser focused on one style isn’t a great idea. And that trying to time the market on what style outperforms when is a losing game, much like trying to time the market in general (the short version is, it doesn’t work).

As an individual I think what is perhaps as important is to choose a style that fits your temperament and interests. I like the idea of quality firms that can reinvest capital that compounds over time. This is in large part due to laziness. I have no desire to be actively trading holdings, and particularly with smaller cap names, with larger bid-ask spreads, see it as a path to eroding long-term returns. A buy, hold, go work on my golf game approach appeals much more to my temperament. Quality, if at times boring firms, fit that bill more. Some of these may be more “value”; some may be more “growth”.

Investment process

To find these firms, a typical process is to start with quantitative screens to narrow down the universe, before diving into more detailed research. Choose some measures that align to your preferred style - Return on Invested Capital, Operating Margins, Profit Margins, etc. – and see what firms pop up. At the extreme you can make the whole process quantitative and invest purely based on these rules.

I’m going to do things slightly in reverse. Rather than starting with the numbers, I want to start with the story. I have 160 stocks to get through, and I’m not familiar with a lot of them.

So, I’m doing a whistle-stop tour of the FTSE 250 index – a fly-by each firm, which I’ll share here – what the company does, how it makes money, key risks that stand out. Something that goes beyond the generic description on Google but avoids detailed financials and valuations, yet. The goal is to see if this is a story that peaks further interest or not.

From that – and yes, this is going to take some time but I’m in no rush – I’ll have a short list of candidates for further analysis. This is where the financials and valuations come in, and where the process becomes, well, a little looser, but it will generally involve working out how the companies map to the desired style of being a quality firm.

Portfolio construction

With the style set, the next question is how many stocks to hold and how to combine them in a portfolio. Diversification is often called the only free lunch in investing, meaning that diversification can bring higher returns without higher risk. So long as the individual stock returns are not corelated 1 for 1, then it simply falls out of the maths that adding stocks reduces overall risk.

But there is a trade-off between reducing risk and replicating market returns. Most research shows that the benefits of diversification get noticeably smaller once you get to around 20 stocks, but the really big reduction in risk comes from going from 1 to 10[3].3 There is also a question of capacity and how many stocks you can really understand. Someone like Terry Smith at Fundsmith has ended up at around 30 stocks, but I don’t have that capacity. 10 to 15 feels about right for me.

I also want some diversification across sectors. This isn’t going to be a 90% tech portfolio (and it’s the UK, so good look with that anyway) but nor do I need to be restricted by percentage limits on either sectors or individual positions.

One of the reasons for not being too restricted is the advice of cutting your losers and letting your winners run. Simple on paper, much harder in practice – and probably one reason passive strategies do better – but something to aspire to no less. 3i, the UK listed private equity manager, purchased the Dutch retailer Action in 2011. It’s now two thirds of 3i’s portfolio, which feels a little too high for an individual stock, but this one investment has driven a +1,000% increase in 3i’s share price over the period.

Risk management

With that all done the final consideration is managing risk.

There are a few ways to think about risk. There’s the risk to the portfolio that the market goes down and it’s nothing to do with what you own (the beta), and then there’s the risk a company you do own blows up and it’s everything to do with it alone (the alpha). There’s also the risk that you can’t buy or sell when you want to, or you can, but it’s going to come at a cost (liquidity).

Most of the approach to this falls out of the above. I’m happy to accept general market volatility because this is an equity portfolio. If I don’t want the beta, I’ll just keep everything in cash. And I’m happy to tolerate a higher level of volatility than owning the broad market because I want a concentrated portfolio. And I’ll accept that brings the chance of a blow-up on any one position because what is public is public, and what isn’t isn’t, meaning you never really know the full story. The key will be getting out of the position if the fundamentals change.

Finally, the FTSE 250 should be liquid enough for my meagre investment amounts, although I’m intrigued to see how bad the transaction costs are, especially as an overseas investor into the UK.

So, there we go, a high level and basic approach but I think it should work for setting some guardrails.

In coming weeks, I plan to return to some bigger picture topics while working my way through the FTSE 250. You can read my thoughts on the first five firms here.

IMPORTANT: This is not investment advice. It is my opinion only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any stock or invest in a particular investment style or strategy. You should do your own research and invest according to your own financial circumstances.

There’s been a proliferation of “factors” in recent years i.e. characteristics that explain returns. But there’s now a growing body of evidence that suggests most of these are nonsense, supporting my general view that the investment industry often tends towards complexity for the sake of complexity. See Factor Zoo. Swade et al. The Journal of Portfolio Management. 2024.

Various academic studies on this. For recent numbers see Peak diversification: how many stocks best diversify an equity portfolio. CFA Institute. 2021. Some of the evidence is also summarised in this post.

This is a great point - and the fact that it's not in probably points to my underlying cynicism over whether anyone can actually have a sustainable "edge", at least in the classic stock picking sense and relative to the collective wisdom of the market. For me this is as much about the process as the outcome. But you're right that I should think about this more... If pushed I think individuals can have an edge in the small cap/lower liquidity space, not necessarily because of better information, but because of less attention from others. And then I think there is an edge (in terms of outperforming a benchmark) you can have by taking a concentrated approach. So the outperformance comes less from better analysis skills and more from overall portfolio construction. But we'll see, I may change my mind!! What do you focus on?

This is a good post about setting out one's approach/strategy.

But what about the next step, to determine how one has an Edge to deliver outperformance?

If there is no Edge then one is better to outsource the investment process. Either to passive ETFs or active managers with Edge.

Edge could include:

- expert knowledge of an industry

- ability to invest shares that others don't touch (small caps, low liquidity, non(ESG compliant, bargepoled)

- better analysis skills than other investors

- better access to information than others. And able to process it effectively.

- faster to trade, decision making.

- strategies that have lower competition.

- etc

It is critical for individual investors to figure out what sort of Edge they want to develop, before getting stuck into building their own portfolios.